Proto-Indo-European: A PIE in the Sky?

An Objective Look at Paleolinguistics’ Most Controversial, Most Polarizing Hypothesis

The Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) is a concept central to historical linguistics, proposed as the common ancestor of a vast group of languages spoken across Europe and Asia, including Sanskrit, Greek, Latin, and Hindi. Reconstructed through comparative analysis rather than attested in written records, PIE has long been a subject of academic inquiry. Yet, it faces increasing scrutiny, particularly from scholars in India, where some question its existence as a historical reality. This skepticism frames PIE as a speculative construct—possibly a product of imagination rather than evidence—prompting debate about its validity. This article examines that debate, exploring the linguistic and archaeological data behind PIE to assess its status as a hypothesized language.

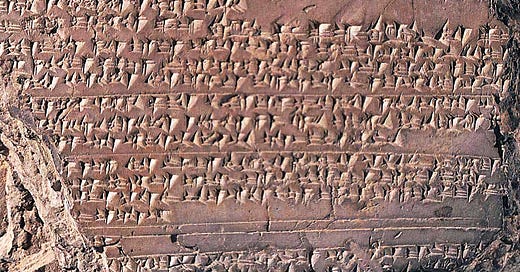

The roots of this scrutiny trace back to 1786, when Sir William Jones, a British judge in colonial India, noted striking similarities between Sanskrit, Greek, and Latin during an address to the Asiatic Society of Bengal. He suggested these languages descended from a shared source, a claim that birthed the Indo-European language family hypothesis and, eventually, PIE. For two centuries, linguists have built on this idea, reconstructing PIE’s sounds, words, and grammar from its presumed daughters. However, the absence of direct evidence—no inscriptions or texts in PIE—fuels doubt. Critics ask whether these similarities could arise from contact, borrowing, or independent development rather than a single ancestor.

In India, skepticism often carries additional weight. Sanskrit, enshrined in ancient texts like the Rig Veda, holds a revered status as a cornerstone of cultural and linguistic heritage. For some Indian scholars, the notion that Sanskrit derives from a reconstructed PIE—often linked to a distant steppe origin—challenges its primacy. This perspective is compounded by historical context: Jones’s work emerged under British colonial rule, raising concerns that PIE might reflect a Western agenda to reframe India’s linguistic past. Such doubts align with broader critiques questioning whether PIE is a testable hypothesis or an unprovable abstraction.

The debate hinges on fundamental questions. If PIE existed, what evidence supports it? How do linguists reconstruct a language never recorded? Can shared features among Indo-European languages only be explained by a common source, or are alternative explanations viable? Beyond linguistics, does archaeology provide corroboration, or does it complicate the picture? These questions are not merely academic—they touch on identity, history, and the reliability of scientific methods applied to the past.

This article hopes to settle the debate to the best possible extent using all available evidence. We’ll start with the theory’s conception, then trace its development over the years, going through all the changes and new ideas along the way. Also, along the way, we’ll get a quick tutorial on all the linguistic ideas of relevance, such as phonetic terms and concepts like Grimm’s Law. Then we will endeavor to get a clear picture of all the arguments against it and those for it, before finally drawing conclusions. In keeping with the tradition of objectivity here, equal space will be accorded to voices from either side of the argument.

This structure aims to provide a comprehensive evaluation. Each section builds on the last, grounding the discussion in established scholarship while remaining open to critique. The goal is not to prejudge PIE’s existence but to interrogate the evidence—linguistic patterns, sound laws, artifacts—systematically. Whether PIE emerges as a concrete language, or a contested hypothesis depends on how this evidence holds up under scrutiny.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Schandillia to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.